The Great Geordie Space Race : The Blog

Last updated : 27-Apr-24

Welcome

This section of the web site contains a small collection of thoughts and essays published over the last decade or so. They're in chronological order with the most recent posted right at the top. Yes, there's a gap of more than two years between some posts. I've deleted a few of the more contentious articles and one or two that were just plain dull. Enjoy.

Last updated : 27-Apr-24

Something wonderful...

27-Apr-24

Last year, whilst lecturing to Croft Local History Society, we were the victim of a petty theft - someone walked off with one of our precious projectors.

This was our spare unit, kept on hand in case the bulb in the main unit pops or just won't work. Whilst this is rare, it's to be expected when the equipment is used on a fairly constant rotation so to loose our spare was annnoying but didn't put us out of business. That said, I was pretty upset for days because you just don't expect this sort of hateful crap when you're out talking to groups of intelligent, interested people. So it hurt.

Now, the good people at Croft were certain that some kind soul has simply tidied the unit away on the assumption that it belonged to the hall and not to the visiting lecturer. Stuff like this happens. You get used to it. Hence, they pretty much ripped their store room apart although, sadly, were unable to locate our projector.

Skip forward nearly a year and, surprise, surprise, the unit turned up last week following a routine tidy-up of said storeroom. They called me straight away and we went to retrieve the unit the next day. Their conclusion : somebody had indeed stolen the projector and then brought it back surreptitiously. Perhaps their conscience got the better of them.

Back at base, I checked out the unit but noted the following:

1. The case was a slightly different colour, as if it had been stored in bright sunlight 2. The unit had an unusual smell about it. Not tobacco. Something else I couldn't quite identify 3. The mains cable was coiled differently. I never knot cables. It makes them prone to snapping internally

So, yes, I have to conclude that the unit had been stolen and used for a time. Later, the perpetrator returned on the quiet, in the hope that their mistake hadn't been noticed.

Personally, I'm just pleased to have it back. We now have two spares, thanks to a friend who happily donated his old, unused unit.

Stuff like this happens. You just have to smile and get on with the job. It's part of the routine. Doesn't make me feel any better about it though. We'll keep on doing what we do so long as stealing our vital kit doesn't happen too often.

Last updated : 27-Apr-24

The North Tyneside Solar Trail

18-Mar-24

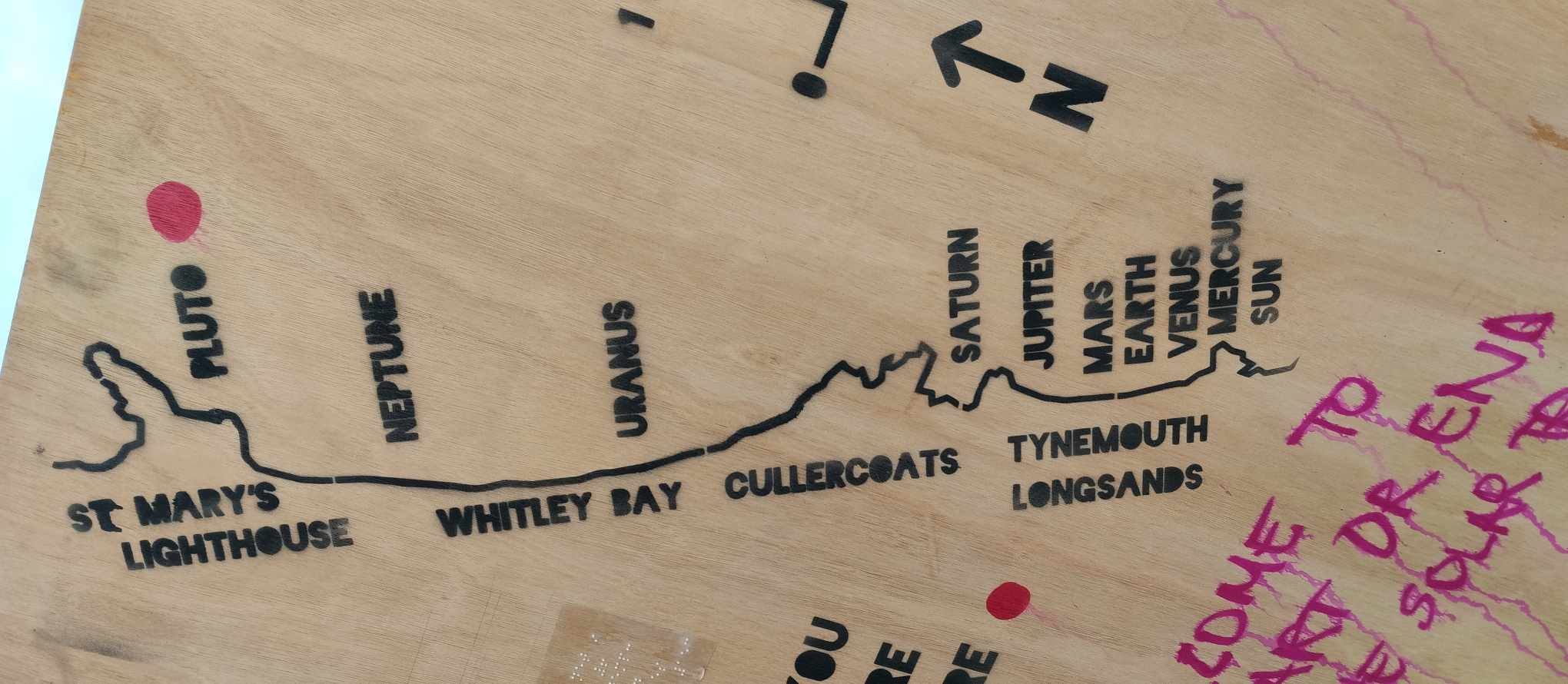

I took a trip into Tynemouth this morning to participate in the North Tyneside Solar Trail, a one-billion-to-one scale model of the solar system laid out along the north east coast between Tynemouth and St. Mary’s Lighthouse. Luna Astronomical tried to do something similar along Northumberland Street in Newcastle with BBC Look North more than a decade ago but, alas, Newcastle City Council didn’t respond to our e-mails so it didn't happen. Such is life.

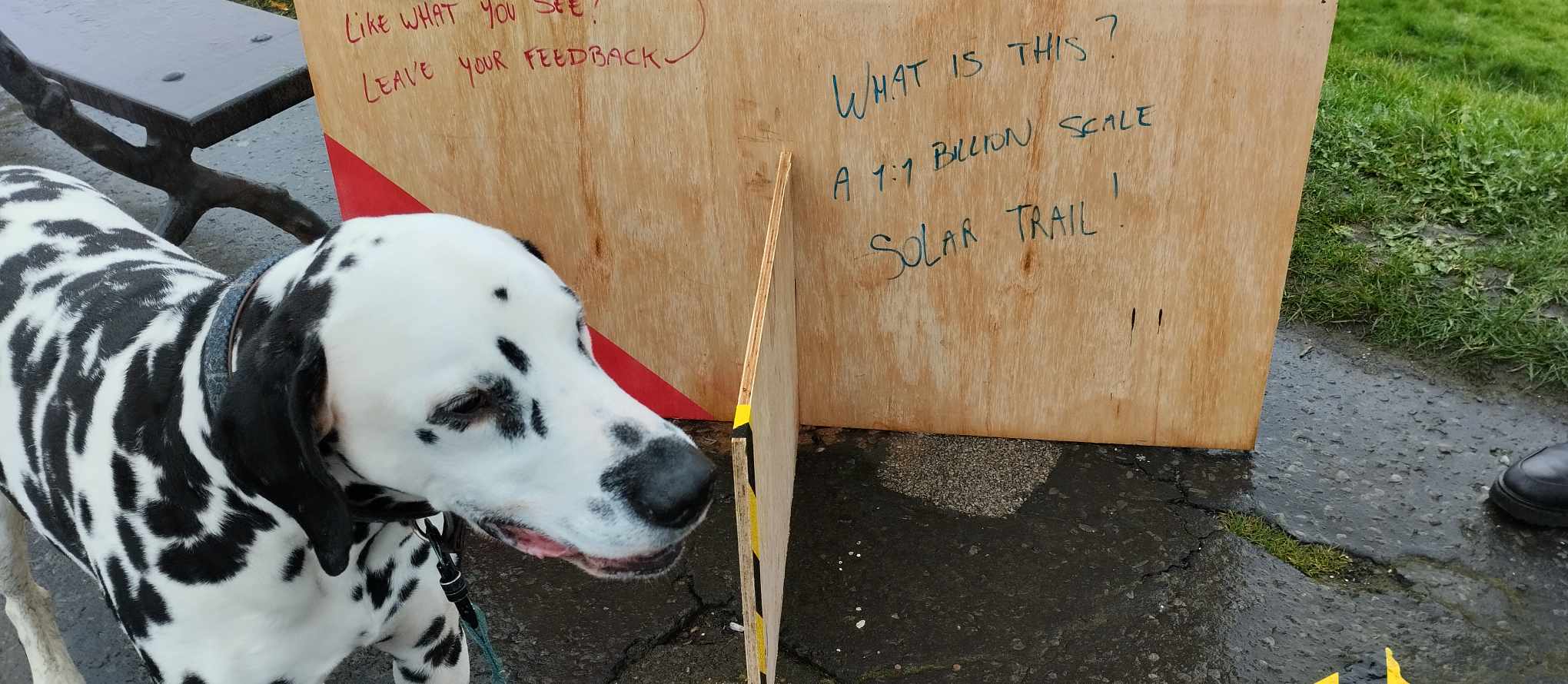

Rather than make the journey on my own, I took Jasper, our Dalmatian. Whilst Jasper cares absolutely nothing for astronomy he’s good company even if he pulls a lot and craps on the occasional putting green.

Our journey began with the Sun, which was perched high on the cliffs above King Edward’s Bay. You could, of course, start at the other end of the trail with the planet Neptune, which was just past Whitley Bay and right next to a conveniently placed car park. Those of the Old School, who feel that Pluto should still be considered a Major Planet, could alternatively start their journey next to the causeway that leads to St. Mary’s Lighthouse.

With the Sun at our backs, we proceeded north although we hadn’t gone more than say 50 meters when we came across the diminutive Mercury, so small in comparison to its parent star that I did actually miss it. At this scale, it’s little more than a grain of rice anyway.

How's this for a thought experiment? Suppose you’re standing on the surface of Mercury and the visor on your space helmet is thick enough to deflect most of the Sun’s rays without melting. The Sun would occupy around two degrees of the sky, which is roughly four times the width of the full moon. That’s whole lotta sky there.

Moving on, we soon came across Venus and then Earth. At this scale, that’s when you start to realise that the rocky planets really are bunched up together in one place. Mars was next and completed the quartet of inner planets. You’re now standing more or less on the outer edge of the Goldilocks zone, the habitable region around our star. It’s not very big, is it?

Once we’d cleared Mars, Jasper and I made ourselves ready for the jump towards Jupiter, Jasper by way of a couple of dog biscuits, me by way of a healthy-snack bar thing that got stuck in my teeth and irritated for the rest of the day. At some point, by my reckoning somewhere fairly close to the Sea Life Centre, we crossed the Asteroid Belt, that region in space where the pull of the Sun’s gravity closely balances that of the planet Jupiter such that this region is devoid of large planets. It's a common misconception that the Asteroid Belt is nothing more than a seething cauldron of tumbling boulders, each the size of Mount Everest. It isn’t. We routinely send space probes through this region of space and, thus far, we haven’t lost one. Yet.

At this scale, Jupiter sits just opposite St. George’s Church on the Tynemouth Sea front. It’s there that I met one of the co-organisers, Graham Edwards, and we had an interesting exchange about the number of visitors (between 1500 and 2000) and their apparent enthusiasm for the project. Jasper made himself a new friend, too.

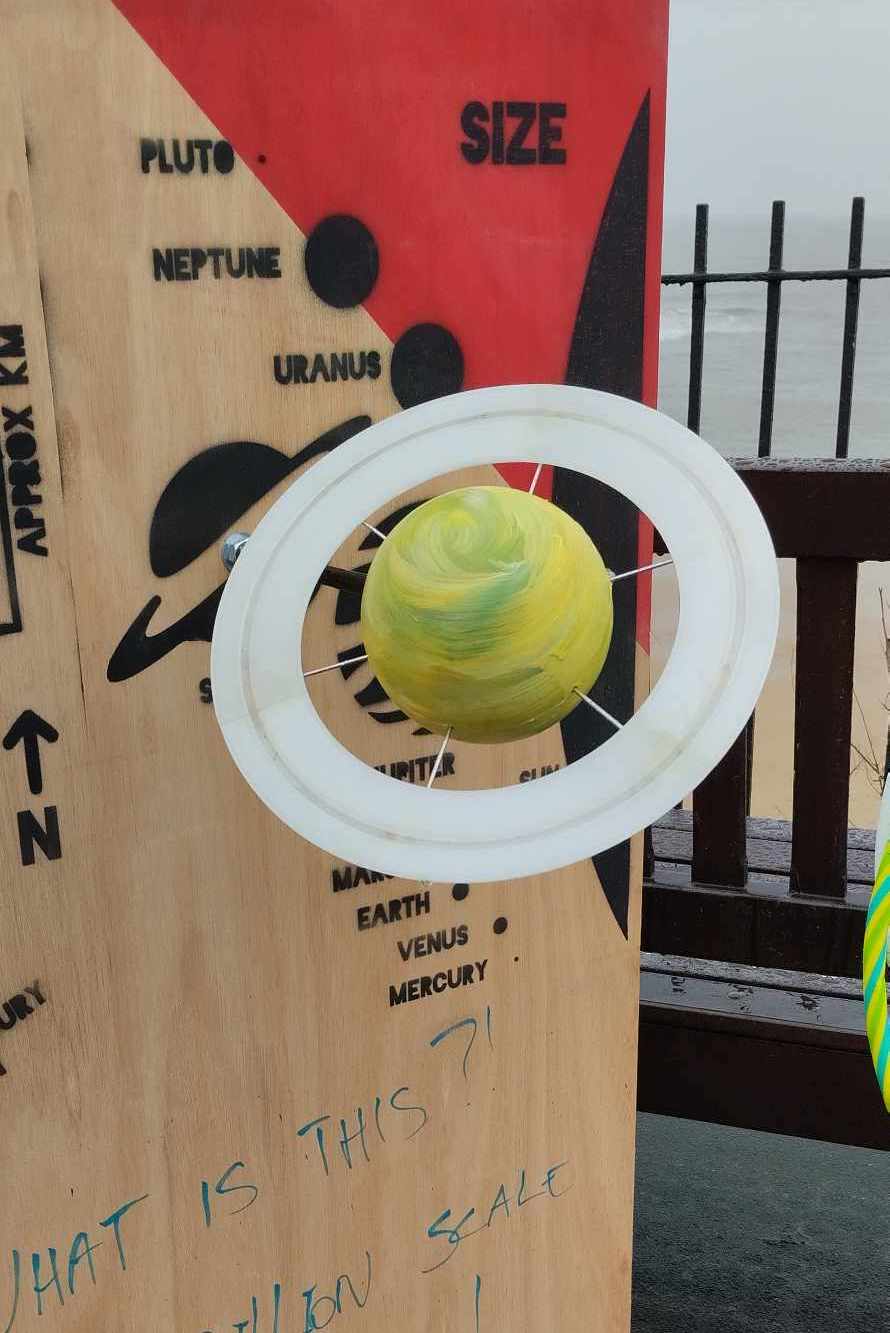

Next came Saturn, which we found just above the cliffs at the head of Cullercoats Bay. David Majarich was on hand to talk about the ringed planet and to discuss the viability of a permanent installation. We interviewed David and Graham on GGSR-05 so it was finally good to meet up.

At this point, I started to feel tired. I’d spent the previous day doing DIY in the back garden and my knees were painful. Hence, the trip out to Uranus was starting to look more than a little daunting. Jasper and I set off at a reasonable pace and soon reached Whitley Bay beach. A visit to the toilets was in order. I realised I’d needed a pee since Mars, which is not a sentence I had anticipated when I got out of bed that morning.

With Saturn a long way behind us and Uranus still some way off in the distance, I wondered how fast we would be going if we stuck to the same one-to-one-billionth scale. It takes light around two hours and fifty minutes to travel the distance between the Sun and Uranus. I’d covered the same distance in around an hour albeit with one or two stops to talk to fellow travellers, and to clean up one of Jasper’s deposits. By my very rough calculations, I was travelling at approximately three times the speed of light. In comparison, it took Voyager Two nine and a half years to travel the distance between Earth and Uranus. Another interesting thought experiment, no?

I found Uranus on the sea front although the station appeared unmanned. Somehow, I forgot to photograph the board. My bad. At this scale, Uranus is little more than a Ping Pong ball. I did wonder what William Herschel, who discovered the planet on 13th March 1786, would have made of this exercise.

Somehow, I completely missed Neptune and continued on my way towards journey’s end and St. Mary’s Lighthouse, where I hoped to find both Pluto and my lift home. Jasper soon found the board marking Pluto (and pee'd on it!) although someone had actually stolen the 3D printed model - no doubt a purist who reckons that Pluto should not be included in such august company having been demoted to the status of a Minor Planet more than a decade ago. In terms of scale, Pluto is about the size of a pinhead, which probably corresponds closely to the mentality of the individual who swiped the model.

Alas, like lonely little Pluto, my lift was nowhere to be seen. That’s when I spotted one of my fellow travellers, who very kindly told me where I could find Neptune. It was, apparently, on the corner of a large and fully occupied car park so perhaps I could be forgiven for missing it.

My lift turned up and we set off home, glad to have made the journey but a little disappointed to have missed Neptune. Then, thanks to the horror story that is the road network to the north of Whitley Bay, the car ground to a halt. And there, just ahead of us, was the board marking the position of Neptune. Talk about serendipity. We dumped the car whilst I hopped along the sea front and took a couple of awful selfies.

Elated, we set off home. Everyone was happy except Jasper. He’d been demoted to the rank of Ensign for pooping on a Putting Green, despite being told not to.

The North Tyneside Solar Trail was a lot of fun and a smashing way to spend a Sunday morning. Whilst I walk our dogs (nearly) every day, it’s not often I embark on a walk with such a strong science component. Was it entirely successful? As a means of figuring out stuff in my head, I still found it hard to visualise the scale of our solar system properly when the four rocky inner planets are bunched up so close together and then there's the enormous distance between them and the first of the gas giants, Jupiter. Part of that, I think, is because the trail followed the weaving road and you couldn't see where you’d been and where you were going. It's therefore difficult to judge the distances properly in your head.

Would I do it again? Yes, absolutely. Walking the walk and talking the talk feels way better than reading a table of figures from a spreadsheet. Plus... Jasper had a laugh, too. He’s presently curled up in his bed downstairs and dreaming. I wonder what he’s dreaming about?

Let’s hope the organisers receive enough feedback to encourage the council to get behind a permanent installation.

Science Friction Redux

03-Jan-22

Over the years, I’ve lectured at length about science in science fiction films, commenting that there’s actually very little good science in the majority of science fiction movies. Of course, there have been a number of absolutely outstanding films which do the science right - 2001: A Space Odyssey, Close Encounters, Interstellar, Ad Astra, Gravity (within limits) and Ridley Scott’s superlative The Martian to name but a few.

All of those afore-mentioned movies have been big budget films with serious money behind some cutting edge special effects. But what about independently-made films? Or even films with a modest budget?

Alas, at first sight, the general consensus is that independent films seem to fare less well. Without the money to spend on science advisors and CGI, science usually goes out the window in favour of eye candy.

However...

I’ve seen two films in the last week that changed all that. The first was Cosmos. I’m not sure how I found it. I think I was just trawling through Amazon’s recommended list and it popped up under Other Customers have watched...

Cosmos has no big budget and no big stars. Just loads and loads of skill and gallons of pure passion and enthusiasm.

The film is about three amateur astronomers who embark on a late night observing trip in a battered old Volvo estate. The vehicle is crammed with gear and there’s virtually no room to move, a facet that will be familiar to many amateur astronomers and gigging musicians alike.

I’m not going to give away anything about this movie. No spoilers here. Suffice to say that over the next one hundred minutes, you get to discover some of the back story behind the moody exchanges and why the protagonists don’t immediately work together as a team. There’s the human side of the story. The astronomy though? It's good. It's intelligent. It's provocative.

What’s important here is that the science is not the usual over-the-top garbled bollocks one comes to expect in certain programmes of the type that imagine that reversing the polarity of the neutron flow makes any kind of sense. The science is... science. The language is neither complex nor overloaded with technical jargon.

The look and feel of Cosmos is (and without wanting sound like a third year media student) very Spielberg. It’s huge. It’s deep. The editing is pin sharp. The humour is natural and easy-going. In short, the movie just works.

The conclusion? I won’t say much except that... this is why amateurs do astronomy.

I loved the film. In fact, I loved this film so much that I got in contact with the directors, brothers Zander and Elliot Weaver, via Facebook and we’ve enjoyed a few brief exchanges about films and filming. I also spend several happy days over the Christmas break researching how they’d made such an amazing film on zero budget.

The second film, Clara, had a bigger budget but not by much I would wager. It’s a very New Age film and certainly a bit more touch-feely than Cosmos.

The story? An astronomer is obsessed with finding evidence of ET, so obsessed that he hijacks time on a telescope and consequently gets himself sacked. Working in isolation, he recruits an assistant, Clara, and... well... There’s a relationship. And some astronomy. And much of it is good astronomy too. No surprises, the relationship doesn’t work but you knew that already, didn’t you? Because we’re astronomers and we're a bit dysfunctional? But the conclusion? The science? Brilliant and intensely thought provoking.

If you're into astronomy in any way, see them both. Even if you're not into astronomy, see them both. They're worth every single minute. I came away inspired. I went back to my telescope and started dreaming again...

The Parenting Thing

21st October 2021

Two and a half years ago, at the age of fifty seven, I became a father for the first time.

Christopher came into our lives and changed us all permanently, and for the better, too. Hardly a day goes by when he doesn't delight, infuriate, amaze and entertain. He requires a lot of work and immense amounts of patience but the end result is utterly rewarding. It's fantastic to watch his personality surface, as his brain learns and develops. It's hard to stop laughing at the antics and the chasing games although I could do without the water-throwing episodes and finding myself locked in the downstairs toilet.

About eighteen months ago, when Venus was riding high in the evening sky just before sunset, I took the big refracting telescope out to the front of the house and invited Christopher to look into the eyepiece. He didn't. He mistook the eyepiece for something edible and wrapped his entire mouth around my precious 25mm Plossl. It took me the rest of the evening to scrape baby-spit and the remnants of Farley's Rusk out of the eyepiece. He wasn't allowed anywhere near the scope after that.

Skip forward to two weeks ago and the final evening of the Houghton Feast. We took him to visit the fun fair. Chris wasn't impressed. Either he was tired and hungry or just missing his bed, the rides and the roundabouts just didn't engage him. Not at all. Just a lot of noise and flashing lights, and he can get that at home.

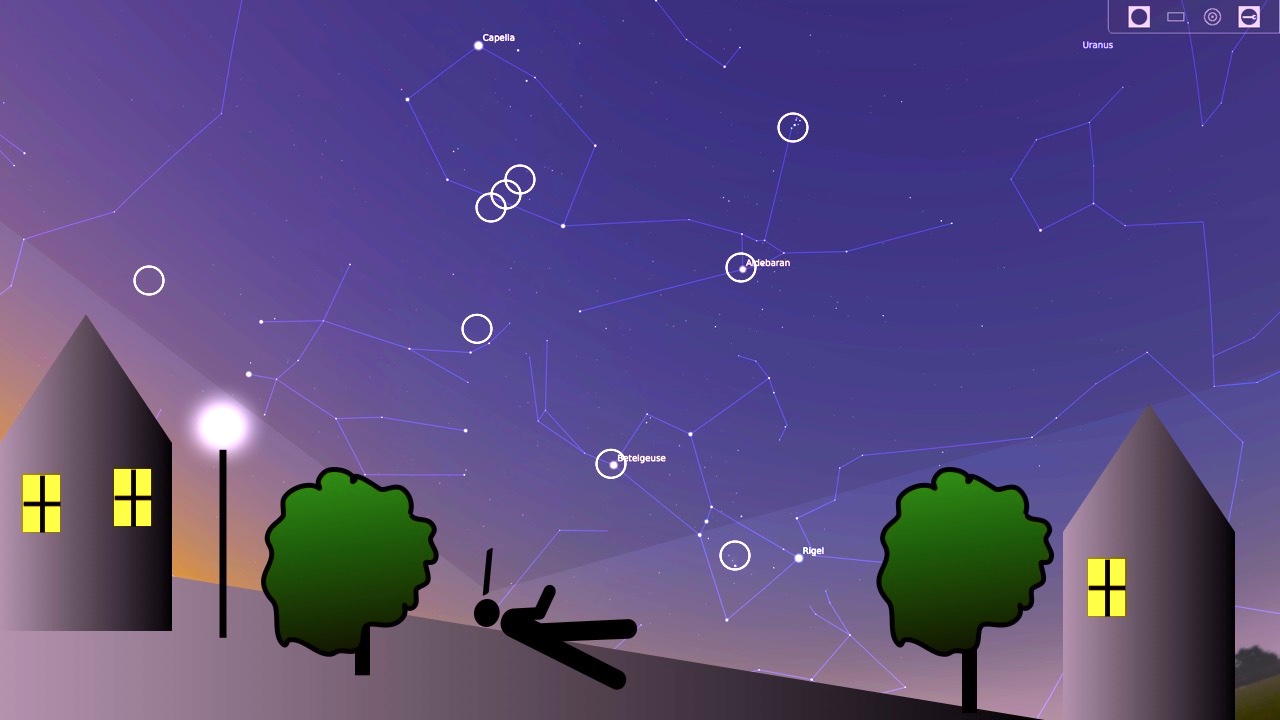

Back at base, the sky was clear and bright, and the Moon was at first quarter. Beneath the Moon lay Jupiter and, to the right and slightly obscured by trees, was Saturn. I wondered if Chris would enjoy the view. I wasn't optimstic but... why not?

I lifted the scope out onto the drive, fetched Christopher's plastic footstool from the kitchen and placed it next to the scope. He didn't require any encouragement.

He clambered up and, with his Mum holding him upright, he got his first glimpse of the Moon through a telescope.

He did a double-take. How could the Moon be up in the sky but also in the eyepiece, right in front of him? He looked and looked again, and then paused and then looked some more. What is this magic? You could see his little brain trying to figure out the puzzle.

I thought he'd get bored quickly. I thought he'd lose interest within a minute. He didn't. I had to reposition the scope three times before he was finally satisfied and, even then, he was reluctant to go indoors.

Ever since then, he has looked up at the scope in its storage location and shouted "Mooo!", which I think means Moon...

... and I can't wait until next month when the next Lunar Cycle begins all over again.

Last night, his Mum messaged me to say that he was lying on the drive, on his back, staring up at the stars, and pointing...

Job done, I think.

The Wonky Sundial

21st October 2021

It’s roughly midday in Newcastle on a cold and blustery October morning and my business for the day is finished. All that remains is the bus journey home. The walk up from the Quayside is a strain because it’s steep and cobbled, and I’m wearing proper office shoes instead of trainers. Worse, I arrive at the bus stop only to see my carriage pulling away. I curse (loudly) and then check my watch, which reckons that I had at least another five minutes. I wonder if time runs at a slightly slower rate in this small corner of the Universe.

The next bus will roll up in roughly fifteen minutes, which is a nuisance because fifteen minutes isn’t long enough to nip into town for a bite to eat or browse Waterstones... but then the weight on my left arm politely reminds me that I’ve already raided Waterstones once today, and twice would be an indulgence.

Okay, so what's there to do other than stand around waiting for a bus that may, or may not, turn up on time? Not much, frankly.

A question forms. Is my watch actually telling the right time? I check my wristwatch against my phone’s clock and they agree, more or less.

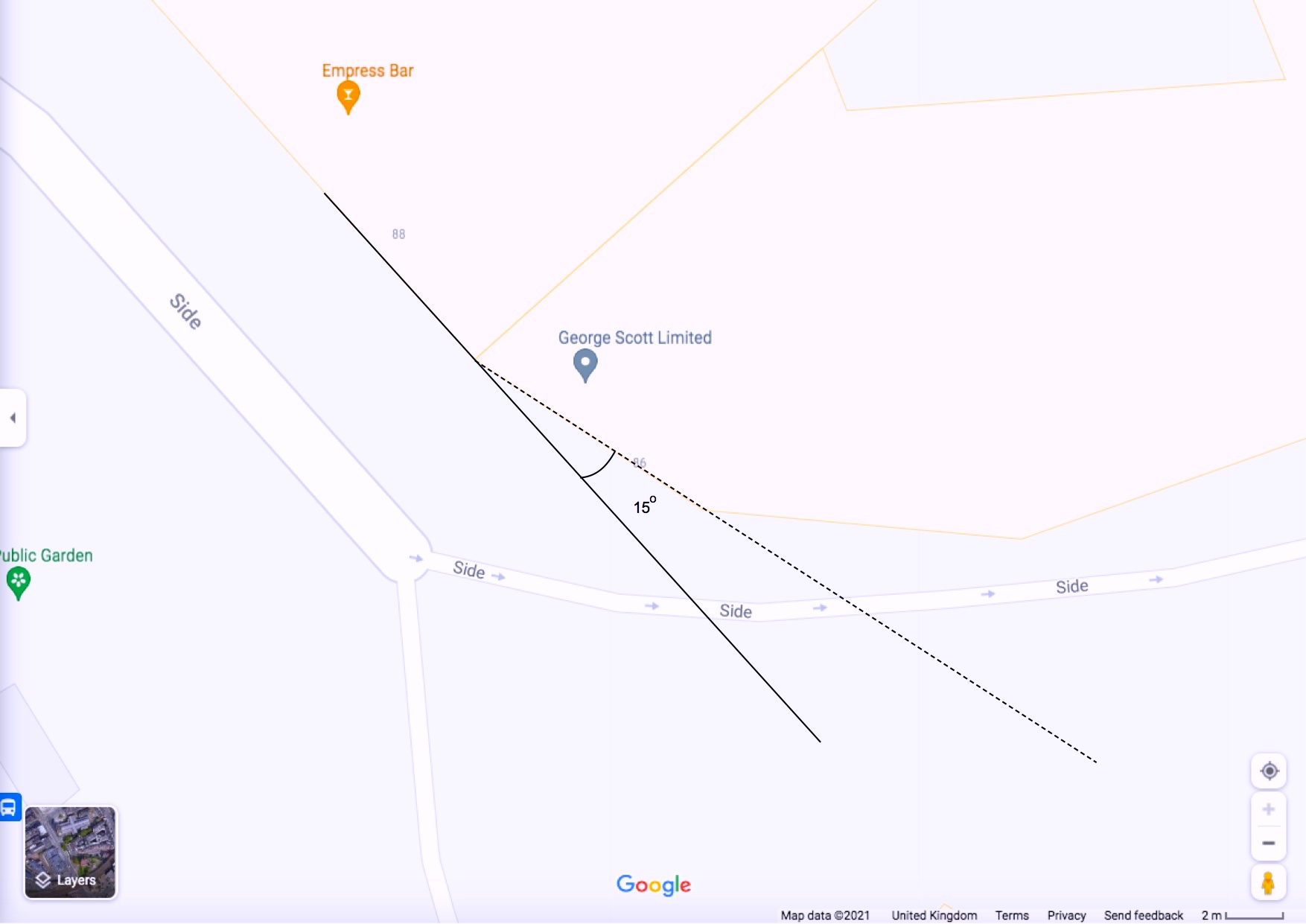

I then check my wristwatch against the sundial atop Admiral Collingwood’s birth place on The Side.

Admiral Collingwood is a local hero. He’s best remembered for taking over from the fatally wounded Nelson at the battle of Trafalgar. Less well known is his long and distinguished career elsewhere. Go look him up on Wikipedia. It’s worth reading.

My wristwatch says the time is 1252 hours. My phone insists it’s 1253 hours. The sundial thinks it’s... wait for it...

The sundial reckons it’s shortly before 1100 hours, say 1050. Huh? That can’t be right.

All astronomers know that sundials offer only an approximation of the current time but... How can it possibly to be two hours behind? That doesn’t make any sense.

Genuinely puzzled, I consult my touchstone in all things puzzling, Dave Newton, and he’s just as confused as I. Eh? What gives?

You see, it’s the first week in October and the United Kingdom is still on British Summer Time. The clocks don’t go back until this weekend, at 0200 hours on the 31st October. Even with the shift back to GMT, the sundial is still an hour behind. How so?

Collingwood being of the nautical persuasion, I contacted a Captain Steve Healy, of the Freemen of Trinity House and asked the same question. Steve reckoned that this sundial had probably been fixed to another building and then later moved to a new location, a common practice back in the day. A quick bit of Googling suggested that the current buildings on The Side were erected around the turn of the last Century and Milburn House, the largest building in this block, was opened for use in 1906. What of the original buildings? They were demolished to make way for this new development. The idea that the sundial is not in its original position is sound.

So where was the original location? Was this the same sundial that had been fixed to the front of Collingwood’s actual birthplace? It seemed likely.

However, the sundial is, at present, exactly one hour out? The number suggests that this might have been done by design rather than by accident.

I checked Google maps but could see nothing immediately obvious. I checked about the web but also came up with a blank.

And then the penny dropped.

If you trace the line of the original buildings which run parallel to St. Nicholas’ Street, you notice that the more modern buildings, to which the sundial is presently fixed, are angled slightly. They no longer run parallel to St. Nicholas' Street, which may have been their original course.

I screen-grabbed the Google Maps image and dropped it into a graphics package. I then drew a line parallel to St. Nicholas’ Street and extended that line so that ran all the way along to the High Level Bridge. I then drew a second line running parallel to the frontage of Milburn House and measured the angle between the two and... The difference is almost exactly fifteen degrees, counterclockwise.

Okay, so a tiny bit of maths... Divide the number of degrees in a circle, three hundred and sixty, by fifteen and you get twenty four. Our days are divided into twenty four equally spaced hours. Fifteen degrees on the sundial is equivalent to one hour.

At a guess, Admiral Collingwood’s birth place was originally situated on the road that ran parallel to St. Nicholas’ Street, with the sundial fastened to its highest point. This building was later knocked down and rebuilt as Milburn House although the angle of the new building was rotated slightly, perhaps to afford a little more day light for the corner offices. The sundial, in its new position of fifteen degrees away from its original orientation, would read exactly one hour behind Greenwich Mean Time.

Now, this is the fun bit. I can’t find ANY reference to this difference anywhere on the web.

If you can find a link then please let me know. I’m genuinely curious.

Thomas Wright’s bench

09-Jan-21

Many years ago, I forget exactly when, I was invited to deliver a talk describing a handful of the region’s astronomers to one of Sunderland’s better known historical societies. I set about investigating individuals such as Thomas Backhouse, the Reverend T. H. E. C. Espin, Robert Stirling Newall and so on. This was interesting research. I’d heard of a few of these men before - Backhouse and Espin were well known but I’d never heard of Newall, even though he’d twice been elected the Mayor of Gateshead and, at one time, had the biggest refracting telescope in the world installed in his garden in a corner of what’s now Saltwell Park.

However, throughout my researches, there was one individual who kept surfacing and re-surfacing, time and time again, and that was Thomas Wright.

Wright was a County Durham lad, born in the small hamlet of Byer’s Green near Bishop Auckland. He was a genuine polymath. A skilled instrument maker and a gifted mathematician, there didn’t seem much that he wasn’t able to tackle with his typical gusto and enthusiasm, and that includes astronomy. His rise from humble origins to the loftier heights of Regency England are well documented elsewhere. He’s best remembered in astronomical circles for his efforts to define the shape and form of our galaxy, the Milky Way, and of his ideas about multiple Universes and life on other worlds. In other circles, he’s best remembered as an architect and one of the first landscape gardeners - a rival to the far better known Capability Brown.

Some of Thomas’ exploits are comical - waking up one night to discover that his employer’s daughter was about to slip into bed next to him, uninvited, for a spot of horizontal jogging and of being accosted on the road to Durham by two thieves intent on robbing him, only for his assailants to find themselves sitting at the side of the road enraptured, as Thomas patiently explained his ideas about the secrets of the Universe. Later, he was dumped, unceremoniously, by a lady, ‘E’, who thought so little of Thomas’ prospects that she found someone else altogether wealthier to marry. 'E' might have kicked herself later on - Wright’s later works were sponsored in part by the Prince Regent and whilst he wasn’t a wealthy man, you only have to look at a list of his acquaintances to realise Thomas moved at the very top of society. Want a few names? John Theophilus Desaguliers (pupil and friend of Sir Isaac Newton and Sir Edmund Halley), Edmund Burke (of Burke’s Peerage), David Garrick (actor and playwright), Samuel Johnson (aka Dr. Johnson), Horace Walpole and Frances Burney.

And so on.

What’s this got to do with a park bench in Houghton-le-Spring?

A few years later I found myself fleshing out a longer and more detailed talk on Thomas, essentially trying to put some meat on the bones of his personal life. As detailed, he became involved with his employer’s daughter and that ended badly. Fearing the wrath of his employer, Thomas ran away and hid for three weeks, and had to be dragged back home to account for his behaviour. After that episode, Thomas jumped on a ship intent on making a new life for himself as a sailor only to discover that he suffered from the most appalling seasickness. He returned to the North East of England and set up a school for sailors in Sunderland, teaching mathematics, astronomy and navigation. When he got bored with teaching, he went to work as an assistant to a local pastor, Daniel Newcombe, whereupon he met Richard Lumley, Earl of Scarborough. Lumley was so impressed with Thomas that he invited him to present his works on navigation to the Admiralty.

And thus began Thomas’ rise to fame and prosperity. If you want to know more then come along to one of my lectures on Thomas. They’re quite fun.

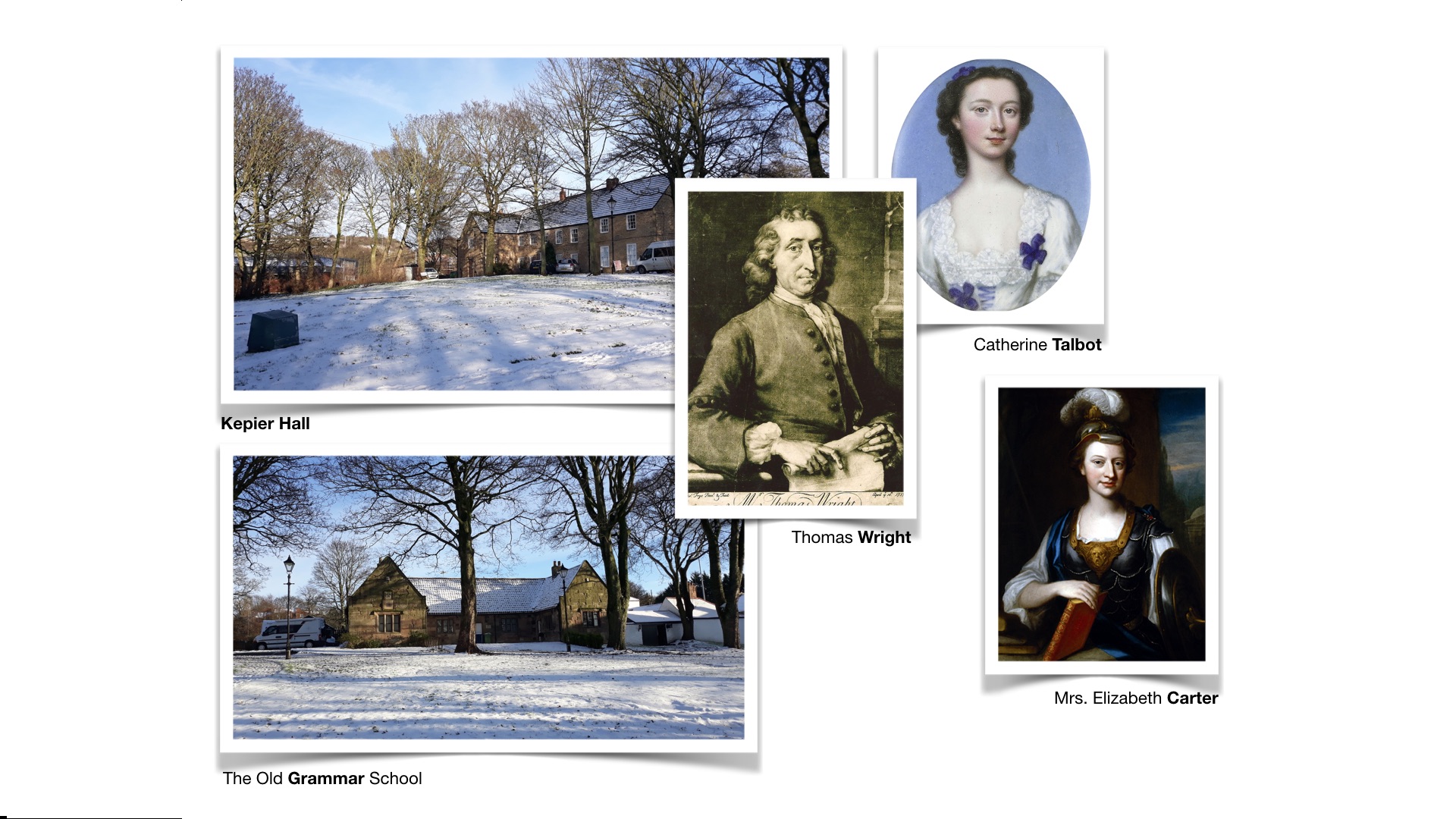

Anyway, it was during my researches into this period of Thomas’ life that I came across two ladies that had some significant bearing upon Thomas and his fortunes.

Firstly, there was Mrs. Elizabeth Carter, one of the Nation’s great poets. She was an ardent supporter of women’s rights and an original member of the Blue-Stocking group (look them up). She and Wright enjoyed an extensive and very intimate correspondence that seems, as far as we can tell, to have lasted many years.

Secondly, there was Ms. Catherine Talbot. Thomas had been Catherine’s astronomy tutor and it was he who introduced Catherine to Elizabeth. The two ladies became lifelong friends and carried on a lively and copious correspondence.

Even though they were officially just tutor and tutee, Thomas does seem to have mixed socially with Catherine more than a little. I was curious about his motives? Was there genuine affection? Maybe an intellectual connection? Or perhaps just an attempt to climb the social ladder?

Sadly, much of their correspondence was lost because Elizabeth Carter’s biographer (a man) took it upon himself to burn most of her more intimate letters after her death fearing that some folk might get the wrong idea.

Now, before we go any further, let’s first define what we mean by the phrase 'the wrong idea', and the words 'close'', 'intimate' and 'companion' in this context. Mrs. Carter said it best. She stated that she openly sought a close, intimate love with her lady friends based on an intellectual attraction and she found just this sort of connection in Ms. Talbot. This does not mean that Elizabeth and Catherine were lovers. Rather, they were intellectually in love and not the rumpy pumpy sort of jiggy-jiggy-stuff that readers of The Sun might enjoy or that might be turned into a BBC4 psuedo-historical documentary with Lucy Worsley in period dress. Those of you looking for a discussion on the relative merits of Sapphic love, perhaps accompanied by some of William Hogarth's raunchier engravings, should maybe take your mind out of the gutter for a moment and look elsewhere. According to Mrs. Carter, the love that she and Catherine shared was founded upon a deep respect and admiration for the other’s intellectual abilities, which were considerable incidentally. Catherine was another founder member of the Blue Stocking group.

Anyway, it was during my researches into Catherine Talbot that I did a real double take. A genuine sit-back-in-your-seat-and-wonder moment...Wow...

You see, Catherine Talbot’s father, Edward Talbot, was the son of the Bishop of Durham. Her Uncle, Charles Talbot, was the Lord Chancellor. However, even though Catherine came from a well known, well respected family, they were poor. Not destitute but poor. Worse, Edward died shortly before Catherine was born and Catherine and her mother were more or less forced to move north to live within the household of Thomas Secker, a friend of Edward Talbot.

This is where the story gets really interesting because Thomas Secker is equally remarkable. Between 1724 and 1727, Thomas was the rector of St. Michael’s Church, Houghton-le-Spring, where he resided in Kepier Hall. Later, Thomas Secker went on to be the Archbishop of Canterbury so...

Here’s the thing. I’d walked past Kepier Hall that morning on the way back from the Co-Op. Kepier Hall sits just behind St. Michael’s Church and immediately opposite what is now Rectory Park.

... which meant that Catherine Talbot was intimately acquainted with the same streets I’d just walked. That’s an astonishing thought.

That afternoon, I took a walk up to Rectory Park and wondered. Catherine Talbot and Thomas Wright had engaged in a lengthy correspondence, and Thomas had a bit of a reputation for developing infatuations where certain ladies were concerned.

Indeed, I wondered, had an infatuated Thomas sat near this very spot and contemplated a future life with Ms. Talbot at his side, as his adoring companion? Was it here, staring into the inky blackness of the sky above the ornamental duck pond, that Thomas had come up with the idea of the Milky Way galaxy? Perhaps in another of Thomas’ Multiverses, far, far away, somehow Thomas and Catherine had hooked up, and had a family of little polymaths of their own?

Sadly, common sense took over and I stumbled back into the bland reality of Houghton town centre on a rainy Tuesday afternoon.

Additional research indicated that Catherine Talbot moved to London in around 1727, when Thomas Secker was appointed rector of St. James, Westminster. She would have been around five or six years old at that point. Thoroughly educated, she later entered Regency society, where she flourished. She began a career as a writer, penning short articles for Dr. Samuel Johnson’s The Rambler magazine although she was never properly published in her lifetime. Alas, Catherine’s health was not good. She never married and died of cancer in 1770, aged just 49. Her major works, Reflections on the Seven Days of the Week and Essays on Various Subjects were published posthumously by her lifelong friend and companion, Elizabeth Carter.

What happened to Thomas Wright? Well, there seems to have been something of a falling out between Thomas and Elizabeth and, by default, Catherine too. He took leave of London and spent around a year in Ireland cataloguing the flora and fauna of that land, as well as investigating many of the local legends of Druids and faery mounds. Certainly, their correspondence ceases, much to Mrs. Carter’s dismay. Thomas returned to England and continued teaching but seems to have dropped Elizabeth Carter and Catherine Talbot completely.

Furthermore, Thomas soon retired to Byer’s Green in County Durham, essentially to finish off his major works. He never married but does appear to have fathered a natural child, possibly with his housekeeper. We’re not sure. His daughter, Elizabeth, carried his surname but there are no records of Wright having married.

And what of Wright’s connection to Houghton-le-Spring? Did Thomas ever visit the place? It would seem likely. We know that Thomas made regular trips between his family house in Byer’s Green and the town of Sunderland. It's likely that he may have ventured as far north as Newcastle too. At that time, Houghton lay at the intersection of two of the region’s major roads, what are now the A690 and the A182, so maybe the notion that Thomas Wright, polymath, did linger near here and gaze lovingly at his former love’s old house, if only to reflect upon what might have been.

Had Thomas walked these streets on a rainy Tuesday not long after Yuletide? Maybe he too had paused outside of The Golden Lion and wondered if the pies were fresh or if they were still watering their ales. Maybe he’d entered the Apothecary to inquire if they had a cure for the Devil’s Ague or a tincture to address a bad case of Jock Itch. Perhaps Thomas, like me, had walked the entire length of Newbottle Street, with his hand clasped firmly over his wallet, lest a shabby Cutpurse from Shiney Row try to dip his pocket.

See? Not much has changed in three hundred years.

iTelescope

08-Aug-20

In my last update, I talked about the urge to photograph the night sky, to capture the very essence of the delights I can see whilst peering down the business end of a telescope. I also talked about my research into astrophotography and about my utter dismay when I discovered the mountain I would have to ascend in terms of time, energy and money if I wanted to achieve even moderate results. Especially money. Yeah, the Big M.

An astrophotographer got in touch following publication of that article and scolded me, saying that it “costs NOTHING like fifty thousand pounds to set up a GOOD astrophotography system. Not even half that amount...” Yes, that’s a direct quote. Do I look like I have twenty five grand lying around?

Anyway, I started to look for a solution and... I found one.

It’s called iTelescope, and it’s a service which connects a large number of telescopes at a variety of excellent sites around the world. How does it work? You set up an account, pay a monthly subscription (fifteen quid) and …. that’s it. You immediately have a brilliant set of tools at your disposal. To take photographs, you just find an available time slot on a free telescope, ideally a telescope that is a good match for your intended target, and ideally a scope that is ‘in darkness’.

Before you begin, it’s a good idea to check the ‘all sky’ camera which most sites seem to support. It will give you a good idea about cloud cover and sources of light pollution. After that, you just let the automation do its job and then wait for an e-mail notification from the system that your job has ended.

I started using iTelescope a year ago and, whilst I haven’t used the service extensively, I’ve been more than delighted with the results. I began with a couple of shots of the Ring Nebula and then the Dumbbell Nebula. They were easy objects and the results looked promising.

Next, I went in search of that perennial favourite, the Andromeda galaxy, selecting two telescopes with different apertures at different sites around the world. I wanted a wide field of view for the first shot and so I selected a simple 100mm refractor based in New Mexico. For the second shot, I was able to snag some time on a bigger instrument, a 62 cm Planewave CDK, based at the Sierra Remote Observatory. Incidentally, this telescope retails for around twenty seven thousand pounds. There’s no way on earth I can afford that but, here it is. I can hire it for around £15 per month and I can buy extra credits if I want to.

I started the exposures off and, roughly ten minutes later, the results were ready to download.

And they were spectacular.

The 100mm showed a wide field of view with the Andromeda Galaxy right in the centre of a field of bright stars. To the lower right was it’s companion galaxy, M101. It’s an impressive image. I’d have struggled to get this kind of image in my back garden even under excellent conditions.

The 620 mm scope delivered a far more impressive result. Have a look for yourself. That's the untouched luminance image at the head of this post. You can make out the dust lanes, the spiral arms, the bright central core and a whole lot more.

So what? You might ask. And, indeed, so what? I sat at home and used by computer to tell another computer connected to a telescope to photograph a region of the sky that’s been photographed a million times before. What was so difficult about that? Well, nothing really. No long drive to a dark sky site. No sitting around in the freezing cold. No frostbitten toes. No soaking wet clothes. Back in time to watch Wire in the Blood with the missus.

I’d like to say that there was no waiting around for the sky to clear but... I did have to wait until the guide star came from behind a lump of cloud. I’d like to say there were no technical problems but that wouldn’t be true either because one of the telescopes simply refused to sync up properly the first time around. Similarly, I’d like to say that the download process was smooth because it wasn’t and I lost a couple of files along the way. Some IT skills were required to navigate the FTP file directories.

It wasn’t at all easy, and certainly not a one-click solution to all of my astrophotography woes. The image of M77, taken from a scope situated in Siding Springs, Australia, was out of focus and, frankly, useless. But at least I didn’t have to leave the comfort of my house to discover this for myself. I didn’t have to grab a long haul flight to the other side of the world. (The cost of a return ticket is around four thousand pounds) More so, I didn’t have to subject myself to the risk of exposure to COVID-19 and I didn’t have to travel into the outback and risks snakes, crocodiles or Australians. That, in itself, is worth the monthly subscription.

What did I do with those images? I’m not at all interested in pretty picture photography. I wanted to do something useful with these exposures and not just stick them in an album or share them on Facebook.

I immediately began to compare one against the other, searching for common reference points. I wanted to see the difference in resolving power between the systems. I was also keen to see what difference the wider field of view would make.

I also began comparing my images with those taken by other photographers, to see what might have changed. Plenty it seems. Some field stars seem way brighter than they should. Others less so. Perhaps. I dunno. But I’ll investigate further down the line.

One of my students asked a very pertinent question “How would you know if you’d downloaded an up-to-date image? Couldn’t they just send you any old thing?” True, and I don’t have any obvious way of figuring that out. At the moment. I wonder if there are any transient features in the image?

Anyway, I got on with analysing the images, studying the dust lanes and the star patterns and a number of the other features.

I was particularly interested in the stars close to the central region. An astronomer on an amateur forum claimed that he’d been able to measure a slight shift in the position of two of the stars close to the core, a claim I found rather hard to believe. Following an initial inspection, I found no such change in any of the central regions but that doesn’t mean that there’s no shift. I just couldn't see it in my images.

So that's iTelescope, the thinking astronomer's tool for photographing the heavens.

A (painful) introduction to Astrophotography

03-Aug-20

Seduced by the never-ending parade of gorgeous astronomy images which flood my Facebook feed every day, I spent some time over the last month trying to summon up the courage to get into Astrophotography in a big way.

At the moment, I'm a dabbler. I can stick a camera mount on my telescope eyepiece and photograph the Moon. I can take time-exposures of the sky and get a blurred image of a comet. I even managed to borrow a solar telescope some years ago and photograph a solar flare. That was fun.

But something is missing. Something has been niggling away at the back of my mind about taking bigger, better pictures, of acquiring the skill set necessary to snap some truly astonishing images. Pin sharp, crystal clear, intense colour. I want to capture the cosmos and hold it in my hand. I want a permanent reminder of eveerything I've seen to help ward of the problems of my failing memory. I want to show these stellar artefacts to my nearest and dearest and scold them. "This is what you're missing..."

So, that's where I'm coming from...

At the beginning, I asked myself three questions:

- 1. How much equipment do I already have?

- 2. How much money will I need to spend on equipment (and what’s it’s resale value)

- 3. How long will it take to learn to use that equipment?

I began by trawling the usual quality publications, The Sky at Night Magazine, Astronomy Now, Astronomy etc, and came away armed with a set of reliable facts and figures, parameters and minimum requirements that might make this project run. In other words, what to look for in terms of equipment, how much it was likely to cost and, critically, what the payback might be in terms of quality images.

Secondly, I went looking at the kind of images I might be able to produce with on a budget of £1000. Not that I have £1000 to play with, mind you. This just seemed like a reasonable starting point.

Finally, I went looking for opinions from experienced astrophotographers. I went in search of recommendations, tips and tricks, techniques and solutions. Youtube, in particular, seemed to be an absolute gold mine of amateurs keen to talk about and show off their equipment.

After a couple of weeks of moderately heavy research, I came away ... despondent. Utterly despondent.

Here are my conclusions:

- 1. Whilst I already have some really nice equipment - a good scope and a good camera - the amount of light pollution in these parts makes practical astrophotography impossible. The question reduces to just one issue - how far am I willing to travel in order to get to a good, dark sky? Fifty miles round trip, give or take, seems reasonable. However, travelling to even the closest dark sky site means a round trip of maybe one hundred and twenty or so miles, in winter, along roads I don’t know well, in potentially adverse weather. Do I want to put myself (and my family) under that kind of stress?

- 2. Unless I spend a lot of money, somewhere in the region of ten to twenty thousand pounds, on mounts, lenses, laptops, guide scopes, a mirror-less camera, then I won’t be able to generate anything worth a damn. And I don’t have that kind of money.

- 3. I already knew that, technically, the field is very, very demanding but this was something else. Simply put, I drowned. I was left adrift on a sea of facts and figures, and conflicting information. The learning curve is steep and unforgiving, and mistakes are expensive.

What else left me despondent?

In the main, what I found was a bunch of photographers taking pictures without any real interest in the subjects that they were photographing and by interest I mean scientific interest. I hope I’m wrong. At best, it seemed to be about pretty pictures and little else. At worst, it was a pissing contest.

Okay, what do I mean? One popular target was the Ring Nebula, a planetary nebula in Lyra. It’s reasonably easy to find if you know where to look. It looks almost exactly like a smoke ring hanging in space. With clear skies, a steady atmosphere and a little bit of luck, you can just about glimpse the star which gave rise to the planetary nebula in the first instance. Some time ago, that star reached the end of its life and blew off its outer atmosphere. This isn’t unusual. It’s a well known phenomena, which has been observed right across the Milky Way. We see this expanding atmosphere as a ghostly, near incandescent shell of gas moving through space. Seen edge-on, it looks exactly like a smoke ring.

We know that this shell of gas is expanding into space. How do we know? Because someone took two or more photographs several years apart and they noticed that the ring had changed. A series of back-of-the-envelope calculations later, and they were able to come up with a rough estimate for how quickly that shockwave is/was moving. And moving it is - about 43,000 miles (about 69,000 km) per hour.

Is this a difficult calculation to make? No. Is it lengthy or time-consuming? No. Does it involve researching an image from say, fifty years ago, and doing a quick comparison, and some maths, and maybe a bit of additional research to check your figures, and a little bit more to estimate the error bars on your estimations? Yes, it does.

And that’s my point.

Nowhere, not once, did I see any of these photographers actually scientifically scrutinising their images, doing the maths, checking the historical databases, researching the images, maybe even publishing a paper (or two). Okay, so they could leave that to a proper astronomer, someone with the time and skills to carry out the work. But my point is... they didn't and this isn’t difficult work.

Worse followed. I watched a YouTube video from a leading expert in the field detailing how you could use a humble DSLR to take pictures of the night sky. I learned a lot. I reckon I could tackle this job for myself and, yeah, I probably will. But why? Why bother? Photographing the Orion Nebula has been done thousands of times before now, and I can look up maybe two hundred or three hundred images showing the exactly same view with a simple Google search. You could, too.

And this is the point in the operation where I started to swear and scream. This same astrophotographer went over the techniques required to bring out the detail in his latest image although this technique mostly involved spreading out the somewhat limited dynamic range of his main exposure to its absolute maximum - without any kind of published method. “Just wing it”, seems to be the mantra of the day.

Could it get any worse? Yes, it could. He actually thought that it was okay to manually adjust the brightness and colour of the brighter stars in the image using Photoshop’s brush tools. His goal? To make a handful of stars more blue - not for any scientific reason but purely for aesthetic reasons. In my view, this isn’t astronomy. This isn’t science. This is deliberately massaging the results to make them look pretty. This is nothing more than high-tech finger-painting.

Annoyed but undaunted, I continued. I found another Beginner’s Guide to Astrophotography by another amateur snapper, although the equipment he described had a combined cost which totalled more than we spent on our first house. A horrendous amount of money... Then I was reminded that this guy and his Youtube channel have affiliate links. In other words, he’s paid by a company to promote their wares on his Youtube channel, something that wasn’t pointed out at the start of the video, something which is probably against advertising guidelines.

In the end, I threw my hands in the air and walked away. I came to the conclusion that I’m happy to leave the advanced photography to the big boys. They have the kit, the time and the energy, coupled with a lot of patience to make it all work ... just so long as they don’t keep doctoring their images to bring out details that aren’t genuinely there.

But, in spite of all of the forgoing, I still want to take pictures. I want to make some truly gorgeous images of the sky. There’s an urge to record the beauty of the heavens and maybe pass on some of that magic to another generation.

So, is there a better solution? Can I still take brilliant pictures of the night sky without spending huge amounts of money or putting myself at extreme risk?

Well, there is... And I'll talk about that next time.

Good Friday

10-Apr-20

Today, 10th April 2020, is Good Friday. We're in the third week of the Lock down.

In years gone by, we'd have followed a small party up to the nearby Hillside Cemetry in Houghton to watch the Passion Play, where a group of overly enthusiastic members of our local congregation pretend to nail one of their friends to a cross. Most years, it's dominated by a bitterly cold North Wind instead of a balmy Mediterranean heat but the cold has never gotten in the way of a thoroughly motivated zealot and, every year, our faux Jesus still stripped down to a loin cloth and then made to walk barefoot through the tomestones. Last year, I couldn't help but think that there was some score-settling going on because those three Roman Soldiers over there looked like they were having a bit too much fun, and that Spear of Destiny was sporting a ferocious tip.

Of course, the timing of Easter has an astronomical significance, otherwise what would be the point of adding it to an astronomical blog?

According to scholars, the date of Easter is defined as the first Sunday following the first Full Moon following the Spring Equinox. Thus, Easter does not fall on any specific date like Christmas Day (December 25th) or The Solemnity of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary (15th August). Easter and its related feast, Accension Day, move around the calendar according to whatever is happening in the sky.

Who came up with this method?

And how are the dates calculated?

It's a complicated business...

The Athenians calculated their dates with respect to a particular Archon or Ruler. The Romans did something similar and referenced all of their historical events with respect to various Consuls. Hence, establishing accurate dates for specific events requires that you know exactly when a specific ruler or despot was in charge. It's a difficult busines, more so when you consider that when one despot takes over from another, all prior works by the previous incumbent are usually obliterated. This means that fixing the date of an event in time is enormously difficult for ancient and medieval historians, and perhaps accounts for why they're such a testy lot, have few real friends and rarely get invited to parties.

The method of computing time from a fixed point e.g. the birth of Jesus has made writing histories significantly easier, to the point where every sensible person on the planet might want to scratch their collective heads and wonder why nobody thought of using this method in the first instance. Those pesky medieval historians are to blame, frankly.

According to the Bible, Jesus Christ's death and resurrection occurred at the time of the Jewish Passover (Pesach in Hebrew), which is a Jewish holiday that commemorates the Hebrews' exodus from slavery in Egypt. It lasts seven days in Israel (and among Reform Jews), and eight days elsewhere around the world. The holiday begins on the 15th day of Nisan, which is the seventh month in the Jewish calendar. It ends on the 21st of Nisan in Israel (and for Reform Jews) and on the 22nd of Nisan elsewhere.

These subtle variations in the Jewish calendar led to different groups of Christians celebrating Easter at different times. At the end of the 2nd century, some congregations celebrated Easter on the day of the Passover, while others celebrated it on the following Sunday. The Christian Church universally agreed was not a good thing and decided to make a ruling.

In 325 AD, the Council of Nicaea ruled that Easter would be held on the first Sunday after the first Full Moon occurring on or after the vernal equinox and predicting the movements of the Moon N years into the future isn't difficult.

From that point forward, the Easter date depended on the ecclesiastical approximation of March 21 for the vernal equinox.

But wait... it gets even more complicated...

Between 325 AD and now, we had a change of calendar... Back in 325 AD, we used the Julian calendar, so named after Julius Caesar - yes, that Julius Caesar - because he was the ruler who standardised all of the calendars throughout the Roman Empire. Makes sense, really.

Insert obligatory What have the Romans ever done for us? joke here...

At the Synod of Whitby in 664, King Oswiu of Northumbria ruled that his kingdom would calculate Easter (and observe the monastic tonsure) according to the customs of Rome rather than the customs practised by Irish monks at Iona and its satellite institutions.

I mention this because perhaps the most respected of scientists, astronomers and historians of that age, the Venerable Bede, lived up the road from us in Jarrow & Wearmouth, and it was his advice at the Synod of Whitby which helped define the method for calculating Easter using the science of Computus, as Bede would have known it. In addition, we have Bede to thank for the name Easter, a name which he seems to have derived from the Germanic Goddess Eostre.

Local legend has it that Bede frequently visited the village of Hoton, as Houghton-le-Spring was called in the seventh Century, whilst on his numerous pilgrimages to Durham Cathedral. Bede was also known to frequent a licensed hostelry thought to have occupied a site near to what is now a branch of the J. D. Wetherspoons chain, namely the Wild Boar, where you may, for a suitable fiduciary inducement, sample one of those same pies that Bede found so delicious. If you can get served at the bar, that is. In fact, Bede wrote in one of his landmark volumes, A History of the English-speaking peoples

"... I beeseech thee, goodly sirs... Verily, do not attympt to visyt yon place (Ye Wilde Boare) on match days, for the buildyng is knee-deep in red-faced and visybly sour Sunderland supporters, anxious to restore their side's mediocre fortunes... Ale is as flate as Ye Witch's Tit but the pies are good though..."

Back to the story...

Great. Everyone is cool. We're all using the same calendar and everybody is in agreement, right?

Sort of...

By the time of the middle ages, it was realised that the Julian calendar had slipped and critical astronomical dates such as the timing of the vernal and autumnal equinoxes didn't match what was going on in the Heavens. What was the problem? The method of calculating Leap Years as defined by the Julian Calendar was wrong. The Julian formula produced a leap year every four years, which is too many. Leap years happen less often than every four years. Disagree? Look the maths up for yourself.

To get the calendar back in sync with astronomical events, it was agreed that a number of days would have to be dropped from history altogether. Syncing the calendars fell on the shoulders of Pope Gregory XIII, who, in 1582, issued a Papal Bull (a decree), which stated that 10 days had to be dropped when switching to the Gregorian Calendar, and the later the switch occurred then the more days would have to be omitted.

Making the jump to the Gregorian Calendar was a confusing process, and created short months with only 18 days and odd dates like February 30 during the year of the changeover. In North America, the month of September 1752 was exceptionally short, skipping 11 days.

Sounds like a good plan, right? Everyone is using the same calendar again and all of the astronomical events tie up!

Not so. It took over three hundred years for every country in the world to adopt the same calendar. The Catholic countries were the first to fall in line, as you might expect. Spain, France, Italy and Portugal all jumped to the new calendar within a year. However, those pesky Brits took over two hundred years to make the change, and whilst those Colonial Renegades across the Atlantic made the jump at roughly the same time as their British Cousins, it's important to remember that certain regions of the United States didn't jump to the Gregorian Calendar for many, many years. I'm tempted to make a Trump-related joke here but I'm not going to.

These days, whilst countries like China and India still retain their original calendars for the timing of religious and cultural holidays, they use the Gregorian Calendar for business transactions.

Do we need another revision? Is our modern calendar out of step with astronomical events? Indeed, there are moves by the English Churches to fix the date of Easter so that it falls on one specific date just to make it better fit the modern world.

Many cynical modern observers, who now cast a doubting eye over the machinations of the Church, have suggested that we should perhaps fix the date of Easter as starting from that point in the year when Easter Eggs first appear on the shelves at their local branch of Tesco since that date is fixed in the calendar with some considerable precision - namely the 2nd of January.

So there's a potted history of the date of Easter.

Finally, I began the day with a bad case of Writer's Block. At first, the words did not come easily, if at all. I felt ... out of touch... That there was something missing, which I couldn't quite put my finger on. Blame this wretched lock down. I had wanted to talk all about some recent observations of the Moon and Venus but... I got sidetracked and the result was this update.

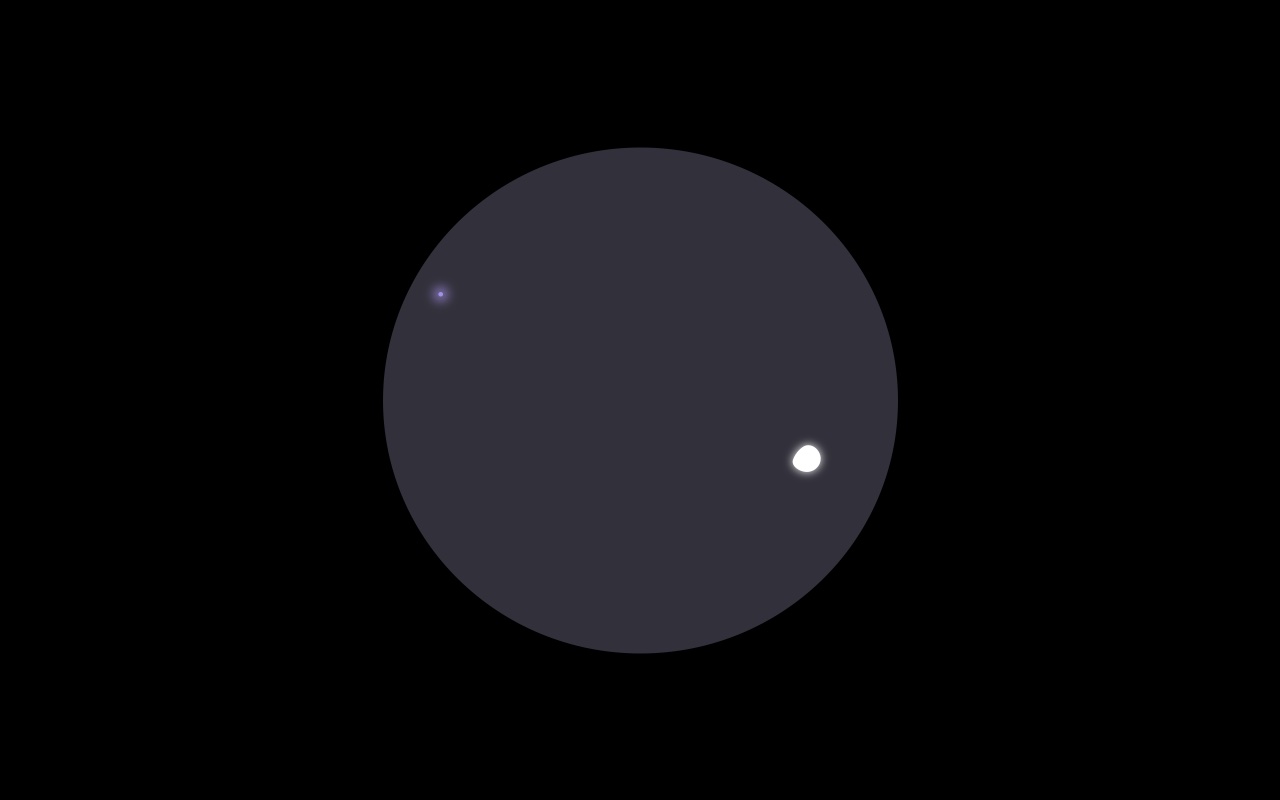

Bowing to pressure from my legions of readers... Okay, just one of you, I'll explain. The photes of the Moon at the top of this update were taken with my mobile smart phone, a humble Samsung Galaxy J5, using a Celestron NEXYz attached to my SkyWatcher 150mm scope. The graphic represents Venus, about two weeks past elongation. I wasn't able to photograph it - the Smart Phone wouldn't lock focus and I got a huge blue every time - so I did the next best thing and rendered it as a crude drawing.

Still... Enjoy.

A Room with a View

20-Feb-20

I was fifteen when I was bitten by the astronomy bug. When I say bitten... well, that's not true. This wasn't like a gentle nip from a playful puppy. I would liken the experience as being more closely akin to that of being mauled by a rather disgruntled Walrus with a bad case of fish-breath. Yes, I was smitten. Utterly smitten. Indeed, I was more smitten with the stars above than I was with my first ever love, Janette Peddar, with whom I had planned to spend my entire future, if only she'd smile in my direction instead of punching me in the guts or sitting on my head at every opportunity. Just once would be nice. Just once...Alas, poor Janette was immediately ousted in my affections by my desire for a six inch reflecting telescope and a subscription to Sky and Telescope.

At fifteen, I had a scope. I had a pair of (borrowed) binoculars. What I really needed was an observatory, somewhere away from prying eyes and difficult questions like "Why bother?" and "Haven't you got anything better to do?". I needed a place where I could practice these dark and mysterious arts without fear of interruption, a locked room where the madness within could hide away from the madness without.However, what I really needed, more than anything else, was a facility away from those who dust, specificially my Grandmother, who insisted that my highly technical and precisely calibrated items of scientific scrutiny required a regular dusting, usually every other day, otherwise... "Where would we be? Some anonmyous Banana Republic. That's where we'd be."

"This is how Empires crumble..." she would grumble as she flitted from surface to surface, feather duster in hand, like a geriatric version of Tinkerbell. "The first thing to go in your typical socialist republic is the dusting." she would mutter to herself. "After that, it's armed insurrection and Secret Policemen on every street corner."

You might be tempted to laugh at the above but, no. Don't. Remember this. Astronomical mirrors are first surface mirrors, which means that the reflective coating is on the front optical surface. They're not like your typical bathroom mirror where the coating is behind the main glass and protected by a thick film of solidified goo. Touch the surface of an astronomical mirror in any way and you WILL damage the aluminium coating.

And Granny did. She swears she didn't but someone did, and she was caught red handed, duster poised in a Ninja-like stance, hovering above my scope. Alas, our duster-intervention came too late and my main telescope mirror was trashed. Those fine-lined sleeks carved into the atomic level reflective coating rendered it all but useless for practical observing. That was an expensive repair job. In the end, I bought a new mirror entirely.

As a response to Duster-Gate, I started to look for a small plot of land away from street lights and off the main thoroughfare but not too far from the house. As luck would have it, I soon found a really good location that matched all of the criteria tolerably well. It was in the middle of a block of allotments near our house and just off the main foot path, with greenhouses on all sides that would pretty much block out most of the intrusive streetlighting. I made a couple of late night reconnaissance trips, hauling myself (and our dog, Brandy) over the rather shambolic wooden fencing that surrounded the enclosure and concluded that, yes, this location would do nicely.

Convinced that this was a good idea, I wrote (what I thought) was a very compelling but friendly letter to the Chair of the Allotments Association, a rather pompous, self-agrandised and very self important would-be dominatrix by the name of Mrs. Irene Betts. I waited a couple of days and then (rather nervously) went to visit Irene in person.

The hauty Irene said that, on the surface, my letter had some strong points and, whilst she had a few misgivings about late-night tresspassers, she was generally in favour of the idea. There were some conditions - the Observatory had to be well used and that it wouldn't cost the Allotment Association any money. Seemed fair, I thought. I agreed that I would pay for, and maintain, the observatory myself and thereafter arrange to pay the rent on a monthly basis just as the other Allotment holders did. Irene agreed to consider my proposal and would let me know in due course. My Grandmother offered to act as a guarantor and her word was a cast-iron promise that the money would be paid on time.

However, weeks went by and I never received a reply to that letter. I went to see Irene in person on at least one occasion but, even when pressed, she would not commit.

Two months later, a bloody great big shed about the size of an industrial container arrived at the entrance to the allotments and thereafter was plonked directly on the site of my proposed observatory. I had my reply.

I was very, very upset. It would be wrong to say otherwise. My mother sympathised and suggested that it was likely a response to my father’s activities when he'd been a City Councillor a few years before. Irene and her friends on the Allotments Committee were, politically, slightly to the right of Atilla the Hun and, to their considerable chagrin, had never been able to bend my father to their will. Clearly some resentment still lingered. Such is life in local politics.

Yes, I was (and remained) pissed at Irene and her passive/aggressive minions for some time to come and, yes, I decided that some form of protest gesture was in order. I mean, this is Astronomy and Astronomy is a serious business. You do not mess with Astronomers. We get mean. Quickly.

There's an old meme which suggests that confession is good for the soul, and it is, after a fashion. Don't worry. I'm not going to confess all of my sins in the next few paragraphs. I'll leave that odious task until Judgement Day, when brain rot and senility having rendered me about as bright as a Cabinet Minister, and poor St. Peter is delegated with the uneviable task of reminding me of what a little git I was in my youth. I may even smile, if I still can.

But, yeah, this is where I fess up to a spot of rather juvenile silliness.

I was in the habit of walking Brandy at around midnight, usually at the end of an observing session or whenever BBC2 had shut down for the evening. And every time I passed Irene Betts’ house, I would swap out the carefully crafted and artfully penned note she’d written for her milkman "Two pints only and a dozen eggs, please." with one of my own.

“The door is open. Come and get some, big boy!” was a common theme.

“I need your special Gold Top this morning, handsome...” was another.

Juvenile? Yes, absolutely. But don't judge me. This was forty years ago and I haven't done anything even remotely comparable since then. Well, certainly not in the last month at least.

At the time, I thought that this petty act of rebellion was incredibly funny although I am not sure what Joe, our milkman, ever made of those notes or if he ever acted upon them. I sincerely hope not. I like to think that he had more sense than to toy with Irene Betts' affections. She did not take prisoners (allegedly).

Skip forward a couple of weeks and the joke had now worn a bit thin but... You know... standards and all that. They have to be maintained. It’s a British tradition. However, on this occasion, something was clearly amiss. There was a light on in Irene's front porch. And was that a shadow lurking just behind the front door? My spidey sense began tingling. The hair on the back of my neck stood up proud and tall, and roundly declared that this rather clumsy deception was likely a trap. Consequently, Brandy and I elected to just sail on past Irene's front door, quickly disappearing into the inky void, binoculars on hand, like thieves in the night.

That was 1978.

Makes you feel old, doesn't it?

Skip forwards a lifetime. I passed through my old village last week as I was returning from a business trip into Newcastle, and the memories came flooding back, as they often do. And they made me smile. The allotments were still there but the shed/container had gone, presumably long since faded into dust. Alas, Irene's precious allotment was overgrown and thick with weeds, as were most of the others but that's nothing new. Those allotments had always been that way or so it seemed. They gave the village the aura of third world, chanty town that had really gone to the dogs.

Alas, Irene passed on to the Great Committee in the Sky several decades ago as did all of her submissives on the Allotments Committee. However, I did wonder if Joe, the Milkman ever kept Irene's Notes and I do wonder if he ever smiled at them. Joe was a man of the world and he had a sense of humour, and he could plainly see through all of Irene's pretentious bluster. I can well imagine the pleasure he might have taken when he eventually presented those minor missives to Irene. "Are these yours?" he might have said in his near-impenetrable Geordie accent. I can well imagine the look on Irene's face. I'm fairly sure that they would have burst her pompous, self important bubble.

I hope so. I really do.

Bang on the money!

29-Jan-20

I am convinced that some considerable time ago, way off in the dim and distant past, the God of Weather and the God of Astronomy were sitting in a bar having a beer or two, or three (you know what these Gods are like) and, somehow they got into a bit of a heated debate over something, I know not what. Maybe an item of bar trivia or whose round it was. Who knows? This heated debate soon shifted up a gear and quickly became an argument, and then the argument rapidly morphed into a bare knuckle fist fight, which spilled out into the street and required the intervention of a Police Officer before peace could be restored. Since then, the God of Weather and the God of Astronomy have never seen eye to eye. Worse, they've never, ever had the stones to sit down, have a chat, discuss their differences and maybe end the evening with an amicable handshake or a friendly game of shove-happenny. And because these two mythical superbeings have never, ever been able to settle their differences, it's us astronomers who have to deal with the consequences.

Don't believe me? Not convinced? It's a story, much like lots of other stories involving mythical superbeings. Take from it what you will.

So whenever a magazine like Astronomy Now or Sky And Telescope makes a knowing prediction of heavenly delights, I always smile and wonder which of the afore-mentioned imaginary deities will prevail. Will I see something? Anything? Or will the event be (once again) clouded out?

As a for instance... Comet C/2017 Panstarrs was supposed to make a graceful flyby of the Double Cluster in Perseus last weekend and, whilst I was able to track the comet on two occasions last week, the actual event was, rather predictably, clouded out.

On Monday 27th January 2020, predictions had said that the planet Neptune (always a tricky target) could be found sitting in the same field of view as the planet Venus. I wasn't optimistic. I hadn't slaughtered any cockrells or bowed down on bended knee before a makeshift altar so... It's my own fault, I guess. I should be more diligent in my worshipping.

However, come 1700 hours, though still slightly hazy, the skies cleared enough to show a thoroughly gorgeous crescent Moon crowned by the equally gorgeous Venus, beaming away at roughly magntitude -4. Yes, that's bright enough to cast a shadow, and it did. I tested it.

Out came the big Skywatcher 150mm scope. Venus was easy to find but also incredibly unstable. So much hot air rising from the ground.

The available maps suggested that Neptune would be in the upper left of the field of a low power eyepiece. I had a quick, furtive look and... well... What's that? Is it a field star? Is it a satellite? No, is it Neptune? Well, it was. Neptune. The bain of John Couch-Adams and George Biddel Airy. (Look them up...)

Jules came out and had a look. It was her first encounter with Neptune and ... wow... that was impressive.

I left the telescope in place and returned, periodically, when I really should have been paying more attention to cooking dinner (which was late. Sorry, Jules) but... you know... Neptune. I have to admit that I was positively bouncing around the room for most of the evening. Finding Neptune under one's own steam is an event in itself. I've seen Neptune once before, at a star party in a group of about twenty, and I saw the taciturn planet for about five seconds, no more. So this was a special moment.

Last night, Tuesday night, I had another go. Stellarium suggested that Neptune and Venus had moved a little further apart in the sky (and they had) but a quick search resulted in another successful find. Once again, pretty thrilling.

And so, for once, the Great God of Astronomy prevailed and we got to see something. It doesn't happen much these days, or that's the way it seems. I want to say that it seems to rain a lot more today than it did forty years ago, and that clear nights seem few and far between at the moment but that isn't true. My observing logs from 1978 strongly indicate that the weather was just as unpredictable then as it is now.

Anyway, Neptune. Still pretty thrilled, frankly. I could get to like this astronomy lark again.

Comet Hunting and Guerilla Astronomy

27-Jan-20

Returning home one night a couple of weeks ago, I was dismayed to find that the family were watching Ru Paul's Drag Race. Think of me what you will but this programme just isn't for me. I'd rather floss the cat. (We haven't got a cat, either)... Alas, it was too soon to go to bed and I wasn't in the right frame of mind to sleep anyway so ... I felt the need to do something a bit more positive, something useful with those precious minutes before the Sandman robs me of my critical faculties.

The good news was the the sky was clear, or as clear as it gets around these parts given that we're marginally less light polluted than Oxford Street in the run up to Christmas. Undeterred and feeling somewhat mischievous, I went outside and tried to find a sweet spot between the two competing street lights and a security light from the Church at the back of our house. I found just such a position but the lights from inside the house spoiled the view a little so, a couple of seconds later, I nipped indoors and pulled shut as many curtains as I could find. Back at my makeshift observation station, I found that these makeshift solutions had worked pretty well. It wasn't dark by any means but it was certainly better.

Then... I discovered that if I got down on my knees then I could blot out a couple of extra lamps, and if I dropped even further I could eliminate another series of house lights altogether. In the end, I found that lying on my back, on our driveway, gave me a more than acceptable view of the sky. Certainly not horizon to horizon but good enough up towards the zenith.

I'd also had the foresight - some may call it hopeless optimism - to bring a pair of binoculars along with me and so I began sweeping the sky for anything of interest. It was cold down on the ground and I was glad of my big, thick heavy winter overcoat and a wooly hat. Never underestimate the restorative power of a wooly hat.

Gradually, as my dark adaption started to work, I began to see far more stars than I have in a long time, and certainly from this location. Casually sweeping the sky brought out some absolute gems. I managed to spot all three of the Auriga Messier clusters (M36, M37 and M38) in one go, and I've never been able to do that from here before. The double cluster in Perseus was another absolute gem. Indeed, that whole area of the sky is wonderfully rich in bright stars and a myriad of tiny clusters.

I shifted my attention to the east and the constellation Gemini. One of my all time favourite targets is Messier 35, an open cluster not far from the star Propus. Jupiter was passing close to this object when I first began observing seriously forty years ago and it's never lost its magic. The cluster itself is fairly loose but I was even more amazed to notice the vaguest twinkling of the nearby globular cluster NGC 2158. It's an easy object in my big Skywatcher scope but not at all easy in a pair of binoculars. In fact, I was fairly convinced that my eyes were tricking me.

Moving further to the east, I found the Beehive Cluster aka Praesepe or Messier 44, which was just gorgeous.

Moving back to the south, The Pleiades were just about to drift over the roof of the house and that view was... just incredible. Thousands and thousands of stars, all pin sharp and blue.

Then something else occurred to me - my astigmatism, which has been a constantly problem in both of my eyes for the last fifteen years, seemed somewhat reduced. Either reduced or perhaps not there at all. The star images in the binoculars were absolutely pin sharp and not the blurred-out rectangles I've been used to. I wondered if lying on my back in a very relaxed state was helping. Later, I checked in with a doctor friend and he was skeptical. Astigmatism does not come and go. Once you've got it, only corrective glasses and/or laser surgery can fix it. However, I did mention that I had not been anywhere near a computer screen for several days and my eyes were almost certainly far more relaxed than they have been in many years so maybe my astigmatism is stress-related. I've seen stranger things.

I persisted.

The Hyades cluster in Taurus was similarly gorgeous and I spent quite a while surveying this region, especially the area around Aldebaran.

Finally, I decided to pay another visit to M42, the Orion Nebula. This one wasn't so easy because it wasn't high in the sky and I had to crane my neck at an awkward angle. I quickly gave up and returned to The Pleiades and then the area through Perseus.

After about thirty minutes - give or take - I started to noticed that I was feeling a little damp, and that the cold was starting to get into my coat and especially the back of my head. This is a good way to catch the infamous Astronomer's head cold, an unfortunate malady of the nose and throat which causes astronomers of all ages to sniff, cough and wheeze, and to casually waft thoroughly grotty handkerchiefs throughout the winter observing months between October and March.

There was also one more nagging possibility pushing at the back of my mind - our Milkman, Ernie, has taken to making his deliveries at around midnight and I had no idea how the poor soul would react if he came across an astronomer lying prone on a customer's driveway. I also had visions of being run over by a milk float and ending up in Accident and Emergency having finished the night covered from head to foot in a heady mix of Gold Top and broken glass.

Back indoors, I wrote some notes - you do right up your sessions, don't you? - before retiring for the night feeling somewhat pleased with myself. Some might say smug even. And they'd be right.

A couple of nights later, we were returning home following a night out and, looking up, I noticed that the sky was a glorious mess of clouds, all skudding in front of the nearly-full Moon. Not much of interest astronomically speaking but still... something about the cloud patterns were interesting. Chris was flat out asleep and thoroughly wrapped up against the freezing air so Jenny I grabbed a decent camera and a tripod, and honkered down close to the ground so that the roof of our neighbour's house obscured the full glare of the Moon. We were then treated to an amazing display of alternating dark and bright clouds, beautiful patterns and shadows which shifted and changed every time we looked away. I've uploaded one of the best images to give you a flavour of what was on offer. Amazing. Truly amazing.

Skip forwards a couple of weeks and Wow... There's a new comet in the sky. C/2017 Panstarrs is not particularly bright but the ephemeris stated that it would pass close to, if not through, the Double Cluster in Perseus. At magnitude +8.5, I wasn't particularly optimistic but, never-the-less, I picked it up from my makeshift observing site on Wednesday January 22nd and again the following night. It was small and fuzzy, as most comets are, but conditions were more favourable on Thursday night when it was certainly not at all star-like and it had clearly moved over the previous twenty four hours.

Alas, last night, Sunday 26th January, it was finally clear enough to get out the big Skywatcher 6" scope and, whilst conditions were not ideal, I did have some wonderfully pin-sharp star images. Sadly, there was no sign of the comet. It had moved on to pastures new.

The moral of the tale is this - despite some pretty horrendous light pollution, you can still do some reasonably useful astronomy. It's also still possible to get a real buzz out of observing even when you have pretty bad astigmatism and I, for one, came away wonderfully inspired. My new observing location has been thoroughly used in the past month and I don't think I've done this much serious observing in many, many years.